(uppdaterad version av bidrag till årets enbladsscenariotävling)

LUSSI BRUD

Översikt: Nutid. Rollpersonerna utreder en folkhögskolestudents försvinnande på en avskild ort i Bergslagen. Det visar sig att den eftersökta har utsetts till Lucia under folkhögskolans lussande. Rollpersonerna snubblar över traditionen på orten att vart 26:e år skicka Lucian till gruvhålet vid Rümmelgården, där varelsen Lussi väntar.

Uppdraget: av någon anledning ska rollpersonerna undersöka var Linnéa, en 22-årig folkhögskolestudent, blivit av. Linnéa går ett folkhögskoleprogram i en liten ort någonstans i Bergslagen. Rollpersonerna kan vara bekanta, släktingar eller vänner till Linnéa och hennes familj, eller externt kontaktade utredare. Rollpersonerna anländer till orten någon dag innan julafton.

Vad vet vanliga studenter på folkhögskolan: De flesta studenterna har åkt hem över jul, men några är kvar. De kan berätta att Linnéa utsågs till skolans Lucia (en tradition som de flesta tänkte var lite ocool för folkhögskolan, men som rektorn drivit igenom skulle genomföras just detta år). Efter lussande på det lokala ålderdomshemmet försvann Linnéa. De flesta tror att hon åkt hem till Stockholm (hon kanske har en kille där?)

Vad vet Linnéas rumskompis Maja: Maja ska alldeles strax åka hem till Örebro för julledighet, men kan berätta att hon inte sett Linnéa sedan 13:e december då hon först lussade i skolans matsal för att sedan bege sig till ålderdomshemmet. Maja är ovillig att svara på så många frågor och antar att Linnéa helt enkelt kommer vara tillbaka på internatet efter julledigheten. Om Maja pressas eller övertalas kan hon berätta att Linnéa haft problem med sitt långdistansförhållande, och att hon har pratat om att hon vill göra slut med Pelle som bor i Stockholm.

Vad vet resten av lussetåget: Linnéa lussade på ålderdomshemmet med framgång (även om de flesta tyckte det var lite töntigt med luciatåg var det också lite fint att se gamlingarnas glada ansikten). Efter ålderdomshemmet mötte Linnéa upp en äldre man som hon åkte iväg med i en gammal Volvo (”det kanske var hennes farfar?”). Ingen har sett henne sedan dess.

Vad vet rektorn Ann-Louise: Skolan brukar inte ägna sig åt Lucia-tåg, men Ann-Louise säger att hon tyckte det var en bra idé i år (”det är ju trots allt många som vill”). Ann-Louise säger sig inte sett Linnéa de senaste dagarna. Om hon pressas framkommer att det var 26 år sedan senaste gången ett lucia-tåg anordnades på orten, då på det numera nedlagda högstadiet, vars lokaler folkhögskolan numera använder.

Vad kan man få veta om skolan på orten: Det nedlagda högstadiet hette Bergsskolan och den sista rektorn på skolan var Jöns Fransson, som fortfarande bor på orten. Skolan byggdes på 1960-talet och ersatte den gamla folkskolan på orten.

Vad kan man få veta om Jöns Fransson: Jöns är pensionerad sedan flera år, och ses som en kuf på orten. Han bor i en liten lägenhet i ortens centrum sedan han förra året flyttade från ålderdomshemmet (på ålderdomshemmet kan man ta reda på att Ann-Louise är Jöns dotter och närmaste anhöriga). Han äger en veteranklassad Volvo. Frans lägenhet är helt tom om rollpersonerna undersöker den; den verkar inte användas alls.

Vad kan man få veta om äldre skolhistoria på orten: Om man gräver i rätt dokument (på internet eller på det lokala biblioteket – som inte har öppet under julhelgen, vilket kanske kan bemästras med list) får man veta att Bergsskolans första rektor hette Pär Fransson (far till Jöns Fransson). Pär var sonson till bygdens starke man Frans Rümmel – en framstående bergsman och kemist under slutet av 1800-talet. Rümmel öppnade den första folkskolan på bygden i början av 1900-talet för att tillse god utbildning för sina arbetares barn.

Vad kan man få veta om Lucia-traditionen på orten: Om man söker i lokala tidningar under en längre tid framkommer det att Lucia enbart har firats officiellt på orten var 26:e år. Vidare sökningar avslöjar att luciorna som utsetts under 1900-talet alla varit utomsockens flickor. Djupa sökningar visar att Frans Rümmel var den som introducerade Lucia-traditionen på 1890-talet.

Vad kan man få veta om Frans Rümmel: Frans Rümmel hade en större gård i bygdens utkant – Rümmelgården – där majoriteten av malmbrytningen utgick från. I en tidningsartikel från 1878 framkommer att en meteorit har slagit ned på Rümmelgården. Vetenskapsmän från Uppsala har varit på plats och tagit prover, men Rümmel har fått behålla stenen.

Vad kan man få veta om man undersöker Rümmelgården: Bergsmansgården är nedgången och stadd i förfall. Trots kylan och snön har lindarna inte fällt sina löv. På gårdsplanen står en gammal Volvo med förardörren öppen och nycklarna i tändningen. Bilen startar inte om nycklarna vrids om. Om rollpersonerna söker runt gården hittar de Jöns Franssons sargade lik i en snödriva – hans gamla kropp har slitits i småstycken. Från ett av gruvhålen hörs en flerstämmig sång:

… Drömmar med vingesus under oss sia,

Tänd dina vita ljus, Sankta Lucia

Kom i din vita skrud, huld med din maning

Sänk oss, du julens brud, julefröjders aning…

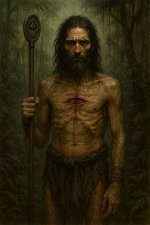

I gruvhålet bor Lussi. Lussi är ett konglomerat av alla de flickor och unga kvinnor som utsetts till Lucia sedan Frans Rümmels dagar. Förvridna ansikten, utskjutande lemmar och frenetiskt pulserande inälvor syns under Lussis vita hud. I Lussis centrum glöder rymdstenen som sammansmälter och håller ihop de lyckliga Lussibrudarna. Linnéas ansikte syns i en av flera armhålor men hon kan inte längre kontaktas med mänsklig kommunikation. Hon är lycklig nu, som en del av helheten som är Lussi. Giftermål är ändå att offra sig och gå upp i någon annan, och vad är bättre än att bli en del av sina systrar i Lussi äktenskap? Lussi kan inte förgöras med mänskliga vapen och om rollpersonerna försöker strida mot Lussi kommer de förintas.

Spelledaren avgör vad Lussis agenda är: antingen kommer Lussi vänta ytterligare 26 år i gruvhålet på nästa giftermål, och fortsätta växa sig stark, eller så har hon vuxit sig tillräckligt stark för att träda fram i ljuset och locka fler unga människor att sammansmälta med henne.